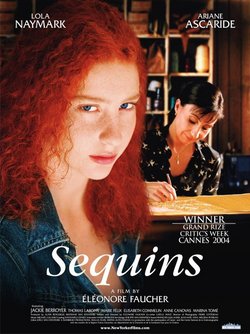

"Sequins": Bold and bright

French film weaves a compelling tale

It's a story that's been told a thousand times: Young girl in a small town gets pregnant, doesn't know how to cope with her new condition. She hides it from her parents; lies and says she's sick to her employer. "Sequins" doesn't even try to put a twist on the old tale. That is, unless one counts subtle, delicate acting, gorgeous cinematography and a heartfelt production a twist.

Which might as well pass as one these days, when explosions and car-jackings are the norm in movies. Eleonore Faucher's "Sequins," in French "Les Brodeuses," glimmers with the performances of Lola Naymark, as the pregnant Claire, and Ariane Ascaride, as the stoic Madame Melikani, two women caught in the hopelessness of life. One woman is young, giving birth, the other old, having just lost her child in a motorcycle accident. Together, they sow the embroidery of their woe and find purpose in its stitching and guidance in its patterns.

It's — oh so French. Yet still, to turn away from the gaze of Claire, as she resolutely deflects her eyes from the ultra sound of her baby and meekly asks to have the sex written on a piece of paper, slaps of neglect. Claire's plight is familiar, her reaction predictable, but the way in which each is portrayed is nothing short of exceptional, evoking sympathy and recognition. Naymark's expressive face, already old with the weight of a baby in her belly and yet young when her childish smile creeps across her lips, reveals the complexities of her character. Each time Claire looks in the mirror at her growing stomach, her eyes subtly shift, from ignorance, to fear, to sadness and last, to acceptance.

Madame Melikani's journey parallels Claire's. The two are brought together when Claire goes to Melikani, a well-known embroider, in search of a job. Melikani, in need of help and companionship after her son dies, takes her in. At first, Ascaride plays Melikani as distant, uncommitted and uninterested. But when Claire reveals her condition to Melikani, the latter can't help but feel sympathetic. The long hours they share embroidering Melikani's designs turn into shared conversations and a sense of communality. Although their friendship and dependency is never overtly stated or tested, it's there, as intricate as the patterns they weave.

Patterns that extend past Melikani and Claire's fabrics onto the screen itself, crafting a movie that's as rich in its usage of color as it is in its acting. Claire's hair is a rich, golden red, her eyes a piercing blue, her wardrobe a collection of soft green and turquoise pastels. Melikani wears a mourner's customary black, but outlines her mouth in bright red lipstick, accentuating the boldness and inner strength of her character. The two women's town, while quintessential in its francophone qualities, also speaks of how small and isolated a village can be. In one scene, an old, rusted ambulance is filmed going up a hill, the grasses of the countryside in the background, its ancient siren blaring in a town where everyone will know, and yet no one will know, about what happened.

The siren's blaring, however, does not just stop with that one scene. It continues throughout the film, hidden under the title of a soundtrack. Michael Galasso, the music director, seems to have not communicated with the rest of the production cast. The music, sometimes soft violins, other times out-of-place French rock and pop, is the sole aspect of "Sequins" that doesn't fit into the film's delicate pattern. The notes stick out, unwelcome thorns in the tapestry, and are a disappointment in an area that could have added much to the film.

But the music can be tuned out if need be, and the acting and images embraced instead. Although "Sequins" ends on an abrupt note, its thread is bound to hold and to extend outside of the theatre well into the night, glimmering with an individuality that is as rare as its plot is commonplace.

"Sequins" (88 minutes, in French with subtitles, at Landmark's E Street) is not rated for sexuality and profanity.

Tags: print

Sally Lanar. Sally Lanar finally is, after four long years, a senior in the CAP. When not canvasing Blair Blvd or the SAC for sources, she enjoys reading, writing short stories and poems and acting. She is also a self-declared francophile and would vouch for a French … More »

Comments

No comments.

Please ensure that all comments are mature and responsible; they will go through moderation.