Student education lost in translation

Parents and teachers struggle to speak the same language to help Blazers reach academic success

Spanish translation below by Veronica Ramirez, Jessica Bermudez and Ria Richardson.

When senior Jose Kafie lived in El Salvador, his parents were actively involved in his education. They hosted a parent reunion, met with his teachers regularly and made time to talk with Kafie about school. However, once his family moved to Silver Spring in search of more opportunities, everything changed.

Now, Kafie's parents must work long hours at several jobs to support the family and are rarely available to talk with Kafie or his teachers about his schoolwork as they once could in El Salvador. The language barrier between Kafie's family and the school makes active parental participation nearly impossible. "It was like there was this huge wall, and they couldn't do anything. They couldn't express themselves to my teachers like they used to," Kafie says.

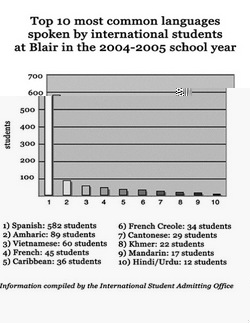

Students all over the county must deal with this lack of communication between their parents and their teachers. MCPS has over 16,000 international students representing 154 countries and 120 languages. More than 74 percent of these families speak a primary language other than English, according to a 1999 issue of MCPS' The Bulletin. Although MCPS has made attempts to make translations available to families who need them, their efforts have not been effective enough to prevent the alienation of non-English speaking families. As a result, these families know very little of what goes on at school and in their children's education.

The great divide

Like Kafie's parents, many Blazers' families must grow accustomed to education practices unfamiliar to them. For senior Abdulkadir Mukhtar and his family, who came to America four years ago to escape civil war in Somalia, the system of education at Blair was entirely new. Before coming to Blair, Mukhtar had spent only three and a half years in school, where he learned minimal English. Mukhtar's fragmented education at these schools was exceedingly different from what he would find at Blair, and when they first moved to the U.S., his mother had a lot to learn. "She didn't even know how to dial phones, how to write a letter or how to communicate with other people," he says.

Board of Education member Gabe Romero says the disparity among education systems of different countries is a source of the problem. "We have to understand where [the parents] are coming from, how they perceive education in their own cultures and what kind of parent-teacher relationships have they had or have not had. That's the beginning of the problem,” he says.

Mukhtar's mother has not let language or her unfamiliarity with American schools hinder her involvement in her son's education. "She didn't have any idea about how the school worked, but every time there was a meeting, she was there,” he says. Mukhtar has the best command of English in his family, so he goes along to each meeting to translate for her.

Blair social studies teacher David West believes that this level of involvement is critical between parents and teachers. "We as teachers are expected to reach out to the parents. Parents are expected to reach out to the school. If parents have the time and are motivated to do this, they do," says West.

To increase communication between home and school, a 24-hour Language Line Service has been purchased by MCPS. The service offers 140 languages translated by interpreters who conduct the three-way conversation over the phone. This service, says Blair ESOL Director Joseph Bellino, is very convenient when a language not spoken by the available faculty at Blair is needed for a parent-teacher conference.

Still, parents who are new to the country often must work long hours to support their families and are rarely available during the time that teachers are, says Romero. Senior Caizhen Li's parents have never personally spoken with her teachers because, she says, they must work 12 hours a day, six days a week. By the time they get home from work, she is already asleep.

This lack of communication between students and their parents makes it easy for students to knowingly keep information about school from their parents, says Beatriz Mendoza, former Blair Community Outreach Coordinator and current Parent and Community Coordinator of the MCPS Division of Family and Community Partnerships. She recalls one student who told his mother that the E's on his report card stood for "Excellent." "These parents depend on students to tell them information, and they don't always do that," says Mendoza.

Lack of parent involvement can also damage students' futures outside of high school, says Mendoza. "Parents don't know what they should know about financial assistance. So because of the lack of information, students don't get to go to college," she says.

The problems are not just academic. When parents are busy with multiple jobs and are out of contact with the school, they often fail to realize when their child gets into social trouble, says Romero.

When Mukhtar found his brother hiding letters from his teachers informing his family of his repeated absences from class, he had to tell his mother. "She only knew when I told her. She had no idea,” he says.

It is harder for students to be successful in school when parents cannot address their requirements, says Romero. "By default, students need someone to advocate for their needs, someone understand how to articulate them. When they don't, they could very easily fall behind," he says.

Importance of empowerment

The PTSA is hoping to attract the Latino community through a parent empowerment program coming to Blair in the spring called "Conquistas Tus Sueños," or "Conquer Your Dreams," which will teach Latino parents how to manage conflicts in the family, better advocate for their children and work with the school system. However, Rothstein admits that the PTSA currently has no way of reaching the families that speak languages other than Spanish. "The PTSA is not doing nearly enough, but we are all volunteers with limited time," says Rothstein.

One third of Blair's population is composed of current or former students in the English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) program. Out of these families, Bellino says he would not be surprised if none had ever been to a PTSA meeting. Rothstein believes the root of the problem rests with MCPS, who she says needs to better publicize resources that already exist in the communities, especially in clusters like Blair with high populations of non-English-speaking families.

For example, MCPS funded the development and delivery of the "Conquistas Tus Sueños" program, but not "one single PTSA leader in the Blair cluster was aware of its existence," she says. The program would not have been discovered by the PTSA if a Latino community activist had not mentioned it to Rothstein.

Mendoza believes that the most effective way to reach out to non-English-speaking families is through establishing meaningful relations between parents and schools. "Yes, it is very hard, but we need to be persistent at reaching parents on a one-on-one basis and providing constant information to them. We can't give up," she emphasizes.

Although Kafie's parents could not easily communicate with others at Back-to-School Night, they left with a favorable impression of the Blair community. "They really liked it, because they said the other people smiled at them. They couldn't talk to them because of the language," he says, "but at least they smiled."

Spanish translation:

Cuando José Kafie del undécimo grado vivía en El Salvador sus padres estaban bien envueltos en su educación. Ellos tenían reuniones para los padres y regularmente se reunían con sus maestros y sacaban tiempo para hablar con Kafie sobre la escuela. Todo esto cambió cuando su familia se trasladó a Silver Spring en busca de oportunidades.

Hoy los padres de Kafie trabajan muchas horas en diferentes trabajos para poder mantener a su familia. Tienen poco tiempo para hablar con Kafie o con sus maestros sobre su trabajo en la escuela como lo hacían en El Salvador. La barrera de lenguaje entre la familia de Kafie y la escuela también hace imposible que los padres se involucren en la educación de sus hijos. "Es como que si hubiera un obstáculo y ellos no pueden hacer nada. Ellos no pueden expresarse con mis maestros como ellos lo hacían antes."

Muchos estudiantes en todo el condado tienen que vivir con la falta de comunicación entre sus padres y sus maestros. MCPS tiene más de 16,000 estudiantes internacionales que representan 154 países y 120 lenguas. En 1999, según MCPS, en más de 74 por ciento de estas familias su primer idioma no es el inglés. Aunque MCPS ha tratado de proveer a estas familias con traducciones, esto no ha sido suficientemente efectivo en prevenir la separación de familias que no hablan inglés. Como resultado estas familias saben muy poco sobre lo que pasa en la escuela y sobre la educación de sus hijos.

La gran división

Como los padres de Kafie, muchos familiares de los estudiantes se acostumbran a una educación diferente a la de ellos. Para el estudiante del undécimo grado Abdulkadir Mukhtar y para su familia, quienes vinieron a los Estados Unidos escapando la guerra civil en Somalia, el sistema educativo de Blair era totalmente diferente. Antes de que él viniera a Blair, Mukhtar asistió a la escuela por sólo tres años y medio en donde él aprendió poco inglés. La educación que Mukhtar recibió en su país era totalmente diferente a la que encontró en Blair y cuando él y su familia se trasladaron a los Estados Unidos por primera vez, su madre tuvo que aprender mucho. "Ella ni sabía como marcar un teléfono, como escribir una carta o como comunicarse con otra gente," él dice.

Gabe Romero, un miembro de la Junta de Educación, dice que la diferencia entre el sistema de educación de los diferentes países es un problema. "Nosotros tenemos que entender de donde vienen los padres, como ellos miran la educación en sus culturas y que clase de relación ellos tuvieron o no tuvieron con los maestros. Este es el comienzo del problema," él dice.

La madre de Mukhtar no ha dejado que la lengua o su desconocimiento de las escuelas americanas impidan que ella se involucre en la educación de su hijo. "Ella no tiene idea de como funciona la escuela, pero cada vez que hay una reunión, ella está allí," él dice. En su familia, Mukhtar es el que tiene el mejor entendimiento del inglés y por eso, asiste a todas las reuniones y traduce para su mamá.

David West, un maestro de Estudios Sociales, cree que este nivel de participación es crítica entre padres y maestros. "Se supone que nosotros como maestros nos pongamos en contacto con los padres. Se espera que los padres se pongan en contacto con la esuela. Si los padres tienen el tiempo y si están motivados a hacerlo, lo hacen," dice West.

Para aumentar comunicación entre la casa y la escuela, MCPS ha comprado una línea telefónica de 24 horas que proporciona ayuda lingüística. Este servicio ofrece 140 idiomas traducidos por intérpretes, quienes conducen la conversación entre tres personas sobre la línea telefónica. Este servicio, dice el director de ESOL, Joseph Bellino, es muy conveniente cuando un lenguaje no es hablado por la facultad de Blair y es necesario en conferencias entre padres y maestros.

Aún, padres recién llegados al país muchas veces tienen que trabajar por largas horas para mantener a su familia y casi nunca están disponibles al mismo tiempo que los maestros, dice Romero. Los padres de Caizhen Li, del duodécimo grado, nunca han hablado personalmente con sus maestros. Ellos trabajan 12 horas diarias, seis días a la semana. Cuando llegan a la casa del trabajo, ya ella está dormida.

La falta de comunicación entre los estudiantes y los padres le facilita a los estudiantes el esconder información escolar, dice Beatriz Mendoza, la ex Coordinadora de Alcance Comunitario de Blair y la actual Coordinadora de los Padres y la Comunidad para MCPS de la División de Familia y la Comunidad. Ella recuerda a un estudiante quien le dijo a su mamá que las E's de sus notas escolares significaban excelente. "Estos padres dependen de los estudiantes para que le digan la información, y no siempre lo hacen," dice Mendoza.

La falta de participación de parte de los padres también puede causar daño al futuro de un estudiante fuera de la escuela, dice Mendoza. "Los padres no saben que hacer para obtener ayuda financiera. Por la falta de información, los estudiantes no logran asistir a la universidad," ella dice.

Los problemas no son solamente académicos. Cuando los padres están ocupados con múltiples trabajos y no tienen contacto con la escuela, ellos usualmente no se dan cuenta cuando su hijo se envuelve en problemas sociales, dice Romero.

Cuando Mukhtar encontró que su hermano ocultaba cartas de sus maestros informando a la familia de sus ausencias repetitivas, él tuvo que decírselo a su mamá. "Ella sólo lo supo cuando yo se lo dije. Ella no tenía ni idea," él dice.

Es más difícil para los estudiantes sobresalir en la escuela cuando los padres no pueden satisfacer sus requisitos, dice Romero. "Por lo tanto, los estudiantes necesitan a alguien que los entiendan y que articulen por ellos. Cuando uno no tiene eso, fácilmente puede quedarse atrás," él dice.

La importancia de autorización

El PTSA espera atraer a la comunidad hispana usando un programa llamado "Conquista tus sueños" que llegará esta primavera. Enseñará a los padres hispanos como manejar conflictos entre familia, ayudar a sus hijos y como trabajar con el sistema escolar. El problema, dice Rothstein, es que el PTSA no tiene ninguna forma de comunicarse con las familias que hablan otros idiomas. "El PTSA no está poniendo el esfuerzo suficiente, ya que todos somos voluntarios con tiempo limitado," dice Rothstein.

Los estudiantes que están tomando o han tomado clases de inglés para estudiantes de otras lenguas (ESOL) son un tercio de la población de Blair. Bellino dice que no se sorprendería si los familiares de estos estudiantes nunca hayan atendido una reunión del PTSA. Para Rothstein, el problema viene de MCPS. Él dice que MCPS debe de hacer público estos programas especiales. Principalmente en escuelas como Blair donde hay un gran numero de familias que no hablan inglés.

Por ejemplo, MCPS financió el programa "Conquista tus sueños" pero "nadie sabía de su existencia," dice Rothstein. Si no fuera por un activista hispano que le habló a Rothstein, el programa no sería conocido por el PTSA.

Mendoza cree que la manera más efectiva para comunicarse con las familias que no hablan el inglés depende de las buenas relaciones entre los padres y las escuelas. "Sí, es difícil, pero necesitamos ser persistentes en dar información constante a estos padres," ella dice.

Aunque los padres de Kafie no pudieron comunicarse con otros en el "Back-to-school-night," tuvieron una impresión favorable de Blair. "Les gustó, ellos dijeron que otras personas les sonrieron. No se hablaron con el mismo idioma," él dice, "pero por lo menos sonrieron."

Katy Lafen. Katy Lafen loves the Beatles, the Rutles and Spinal Tap. More »

Comments

No comments.

Please ensure that all comments are mature and responsible; they will go through moderation.